The World as a Labyrinth

Mannerism

Fantastic Art

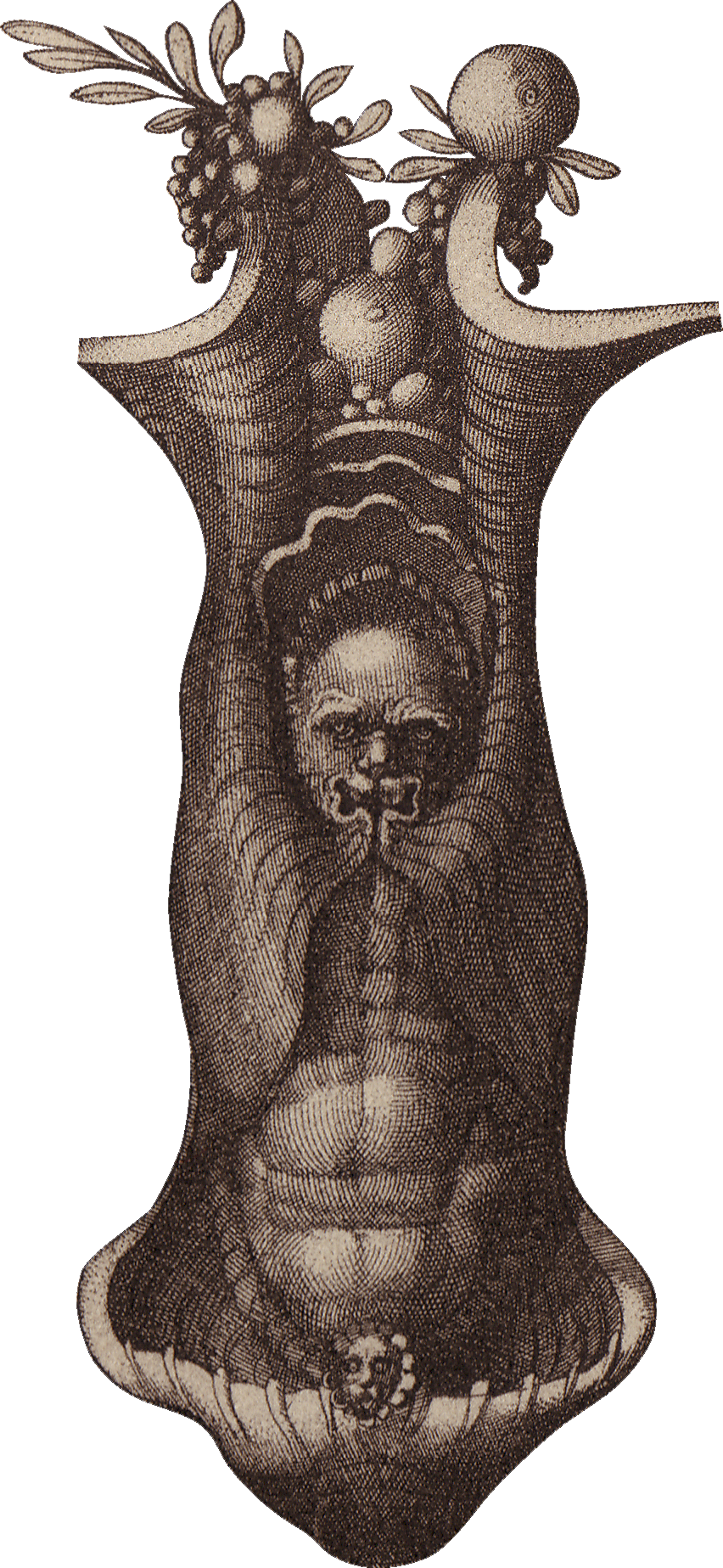

Touristically speaking, the modest town of Bomarzo has little to offer in comparison with nearby Rome apart from a small castle once owned by a prince belonging to that ancient Italian family, the Orsini. Those who enter its gardens, however, will find themselves abruptly transported into a bizarre landscape that seems to have sprung from some demented dream: the Parco dei Mostri, or Park of the Monsters. Gigantic stone tortoises crawl along, cock-eyed architectural follies cower on the slopes, and the paths are flanked by massive urns, rocky grottoes, and grotesque fabulous beasts with gaping jaws. This setting, which no modern maker of fantasy films could improve on, dates from the 16th century. Ultra-modern in its day, the park is an artificial landscape that breaks with the classical forms of the early Renaissance. It is committed to a stylistic trend that was to leave its impress on Gustav René Hocke: Mannerism.

Mannerism is traditionally held to define an artistic period spanning the years c. 1520-1620. It startles and shocks the beholder with a deliberate emphasis on effect. Unlike the early Renaissance, which conveys a feeling of harmony, it strikes discords. Brain, heart and blood are in disequilibrium, says Hocke—in disharmony. This disharmony is fundamental to Mannerism, which to him suddenly becomes far more than just an art-historical epoch. It becomes an attitude to life.

The Mannerist, according to Hocke, is a catalyser: someone who welcomes the changes without which everything would congeal into classical harmony. The Mannerist alarms.5 He is der verdammte Macher—the individual doomed to activity—in whom emotion and calculation merge as they once did in Daedalus, the brilliant engineer of Greek legend and father of Icarus, the youth who soars too near the sun on his artificial wings and crashes to earth. But Daedalus is, above all, the mythical designer of the Cretan labyrinth in which, according to legend, the Minotaur was held captive. Half bull, half man, he was the monster in the labyrinth to whom young people were regularly sacrificed.

To Hocke the labyrinth became symbolic of the Mannerist approach to life. People lose their bearings in it. The laws of the real world are invalidated and space becomes an illusion. Detours become essential staging posts and apparent destinations prove to be dead ends. Labyrinths, which have always been a source of inspiration, probably hail from the Mediterranean area. In religions they often play a role where contact with alien forces is concerned: with the kingdom of the dead or the realm of elemental spirits.6 Hocke believes that the Mannerist sees the world itself as a labyrinth.

A Mannerist work of art is disturbing. It does not appear wholly consonant with its time. Paintings by El Greco or Hieronymus Bosch, for example, make a peculiarly modern impression. According to Hocke, Mannerism must be construed in its aesthetic profundity. Its relationship to the classical resembles that of heresy to orthodoxy. It is related to magic, to alchemy. Great emotions go hand in hand with intellectual games, with Vernunft-Kunst, or reason-art. Mannerism is extreme. It bristles with antitheses, being both wicked and chaste, rational and fearful of a god of wrath. Artificial and exaggerated, it is the expression of a problematic relationship to oneself and, indeed, to society as a whole. Hocke called it the unconscious in the subterranean spiritual history of Europe.7 Mannerism is the necessary antipole to the classical. It points to dangers, disharmonies and abysses, but also to new routes. Europe can derive strength even—or especially—from its dark side.8

Hocke’s immensely wide-ranging knowledge, together with an abundance of hitherto unknown material, enabled him to produce a comprehensive study of the phenomenon of Mannerism. He called it an Ausdrucksgebärde or mode of expression that far transcended its significance as an art historian’s term. Anyone who follows its trail becomes a speleologist, for Mannerism was born in the mythico-religious past midway between Europe and Asia.

Following the route into this abstruse, irregular Europe is like scouting, for no ordnance survey maps exist. Hocke traces it by citing examples from art, literature and music. He delineates the history of a heterodox view of the world from antiquity to the present, via the encoded concetto poetry of the late Renaissance, gnosis, and hermetics: the history of the problematic person.9 In Hocke’s work, Mannerism acquires an umistakable profile for the first time.

Following the route into this abstruse, irregular Europe is like scouting, for no ordnance survey maps exist. Hocke traces it by citing examples from art, literature and music. He delineates the history of a heterodox view of the world from antiquity to the present, via the encoded concetto poetry of the late Renaissance, gnosis, and hermetics: the history of the problematic person.9 In Hocke’s work, Mannerism acquires an umistakable profile for the first time.

More than that, Mannerism to Hocke is a phenomenon common to all times and cultures. He saw it as his mission to demonstrate, by means of examples, a Mannerist constant in European literature.10 But not in literature alone; in the fine arts and music as well. He draws striking analogies—from Bomarzo to Bruno Weber, from Knossos to Niki de Saint Phalle—to prove that Mannerism is an attitude to life rather than a historical epoch. In literature, Jorge Luis Borges shared Hocke’s fascination with labyrinths. Umberto Eco erected a literary monument to Borge in the person of Jorge de Burgos, the blind villain in The Name of the Rose.

To this day, Hocke’s books remain standard works indispensable to an understanding of European art. But to Michael Ende, a friend of many years’ standing, they meant still more: With their help, I became aware for the first time that all that moved me artistically and poetically [...] derived not merely from a fanciful delight in the bizarre and out-of-the-way,´ but from a basic attitude or “primal manner” which throughout European culture—and, indeed, in every culture in the world—occupied a complementary and dialectical but equally valid position vis-à-vis the other, “classicistic” manner. It goes without saying that the Parco dei Mostri at Bomarzo was an obligatory port of call for any visitor to Michael Ende’s Roman villa.

5 G.R. Hocke: Manierismus in der Literatur. Sprach-Alchimie und esoterische Kombinationskunst, Reinbek (1959), 1967, S. 301f.

6 Vgl. G. Hehn, „Labyrinth“, in: Metzler Lexikon Religion, Bd. 2,

Stuttgart 1999, S. 306 ff.

7 Ibid. S. 11.

8 Manierismus in der Literatur, Rowohlt 1959, S. 8f.

9Ibid. S. 304.

10 Manierismus in der Literatur, Rowohlt 1959, S. 21.